At the recent Ivor Novello ceremony, the number one question I was asked was some version of "How does your collaboration with your wife work?" Followed by, "How can you do that without killing each other?"

We were at the awards because our co-written score for the charming animated feature, Two by Two: Overboard, received a nomination for "Best Original Feature Film Score."

We were at the awards because our co-written score for the charming animated feature, Two by Two: Overboard, received a nomination for "Best Original Feature Film Score."

And as our first officially co-written TV series will debut on October 10th, 2021, I wanted to take a moment to answer this question for all time.

But in truth, most everything either of us have done for the past 16 years has benefited from our creative partnership - not to mention two boys, Maël and Eliam, 3 and 8 respectively.

So how does it work?

Knowing Your Strengths

Both Eimear and I are composers, songwriters, lyricists, orchestrators and music producers with decades of music education. We both compose directly into Sibelius so ideas are easily shared.

Neither of us really needs the other to write music, still, both of us have our individual strengths.

Eimear is one of the greatest conductors on the planet having studied diligently at the craft since she was 15. Before Covid, she would conduct as many as 40-50 concerts in a year. She has an encyclopedic knowledge of the orchestral repertoire, she sang in choirs growing up and is a brilliant flutist (although she rarely plays).

Eímear wrote her first orchestral compositions as a teenager and had her choral compositions performed on the radio at only 17. Her music degree is from Trinity College Dublin and she is also being given an honorary doctorate in music from National University of Ireland, Galway.

Conversely, I am jazz guitarist who spent all his formative years writing for and performing in big bands, jazz combos and rock bands. I played string bass in the orchestra in high school but have since lost the ability to play upright. I studied music at Indiana University and my music degrees are from U.C.L.A..

I always dreamed of writing for orchestra but I was out of college before any of my orchestral compositions were ever performed. I am also an orchestral mixer and engineer, which really comes in handy.

So the first characteristic that allows us to work together is that although both of us bring our unique perspective and history to the partnership, the vast majority of our skills overlap.

If the music we have to create plays to either of our strengths, we have the other to call upon for guidance. We are our own best sounding boards and harshest critics. We push each other to write better and call each other out when what we are writing doesn't rise to the level of our joint ability.

Simply put, we are much stronger together than as individuals - even when we don't agree (which absolutely never happens... really, never).

Division of Labor

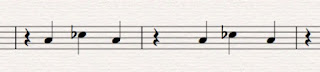

Top of a score page with our shared credit.

The division of labor will take many forms and is fluid based on what's needed for the project. I'll use Two by Two: Overboard as an example.

We will jointly make all the decisions on genre and orchestration so that each of us is drawing from the same models and are writing in the same style.

While composing we will start by focusing on the crucial scenes that required unique thematic material. Having these themes solidified is key so that we can later adapt these themes to other moments in the film, regardless of who is actually writing the music for a specific scene. In this way, I could easily be scoring a scene with a theme Eimear composed, or visa versus.

Then, we will literally split the cues by scene, each of us being responsible for about half the film. We share all the Sibelius files so we might easily copy, intermingle and/or adapt each other's orchestrations and themes.

We often argue over who gets to score what scene as both of us may recognize a golden moment that lets the composer shine. As in every marriage, compromise is vital to preserving a happy relationship - and as in every marriage, "compromise" can also have a fluid definition.

The Recording Sessions

Early in our relationship, I was hired to produce the music for an independent CD that required a small orchestra. Naturally, I had Eimear conduct the session and assist with orchestrations.

Our relationship was relatively new, and of the 40 or so players in the ensemble, maybe half knew Eímear and I were a couple. So when I reflexively started a comment from the booth with the words, "Sweetheart...", the half of the orchestra that knew we were a couple found it endearing while the other half thought I was being a sexist jerk. I think by now everyone knows we are together, I would hope!

Over the years, we have evolved a system that works as follows: In the recording sessions, I'll run the booth, but Eimear really runs the session from the podium. Eimear hears absolutely everything in the room, even with only one exposed ear (the other in a headphone).

So most of the time, I will say very little during the session. My training as a jewish husband well prepared me for this.

Our workflow has evolved this way because even though I will read along as the take is recorded, making notes of things that are outstanding or need correction, invariably, when the take is over, I'll just listen as Eimear makes seemingly every comment or correction I might have noted. If I were to speak up, I'd only slow the process and eat studio time.

It's only if I note something that Eimear didn't hear, or if I have a suggestion that she hasn't already proffered that I will speak up.

Post Production

Although I actually do the physical mixing of our music, the mixes are purely collaborative. I'll get roughs started, and then we will go through every cue together. I will completely rely on Eimear's fresh and fantastic ears to help mold the balances and make sure no element is missed. That extra set of ears is priceless as by the time I have a rough mix together, I'll have at least an hour or two into every cue and one starts suffering mental and aural fatigue.

As Eimear has said many times in the press, our biggest fights are usually over mixes as we both have our own approach to how music should sound. We can usually find a compromise - usually...

As Eimear has said many times in the press, our biggest fights are usually over mixes as we both have our own approach to how music should sound. We can usually find a compromise - usually...

Now the honest part:

We are both highly sensitive creative professionals with strong opinions. Being critical of each other is completely needed, but fraught with the dangers of hurt feelings and bruised egos. That's one of the reasons why it took years for us to finally embrace the idea of creative partnership, despite the fact that it was always there. Co-writing with your spouse will really test your relationship.

Being married to your business/creative partner also means that you can't separate work life from personal life. It all becomes one element. Thus, when things are stressed with deadlines or creative challenges, it effects every aspect of your life. There is no escape!

But when things are sweet - there is a shared experience that I feel is much deeper than if we both had our own unrelated careers. Therefore, when we get the experience of a joint nomination like the Ivor Novello, or I get to go to the Oscars because Eímear has been asked to conduct the orchestra, there is nothing sweeter! I get to experience these things with my best friend. I can't imagine living life any other way.