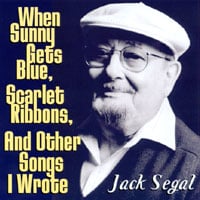

Every now and again, angels enter our lives. February 5, 2005, we lost the angel Jack Segal at the young age of 86. He was writing songs up until the very end.

From his earlier years as a tin pan alley songwriter of the late 40's and into the 2000's, his classics have been covered by everyone from Frank Sinatra, Nat Cole and Tony Bennet, to more recently Barbara Streisand, Al Jereau and Snead O'Connor.

Jack also spent decades as a songwriting coach, holding continuous salons and seminars. Although I was never his "student," he was in every way, shape and form, my teacher. I just got to be the fly on the wall, running the gear as the young tech guy during these lectures, and often I would be asked to critique the songs and productions as well.

In an effort of full disclosure: When I first started working with Jack, I never considered myself a lyricist and when it came to my favorite performances of the classic songs, I barely took notice of the lyric, preferring to listen to the instrumental versions.

I think Jack cured me of this "malady" in the first week of our working together.

The Numbers Game: The Wit and Wisdom

In one of our first meetings, Jack proudly stated:

"In my life as a songwriter, I've written thousands of songs. Out of those three or four thousand, four are perfect. I'd rewrite all the rest. The key to writing great songs is to write a lot of them!"I translate this to one of my favorite phrases: "No Song (or work of art) is ever finished, only abandoned."

Jack stated his four perfect songs were:

Jack's Four Rules to the Perfect Song:

Jack's songs and his rules might seem a bit archaic when you apply them to the latest Billboard chart topper, but when you look deeper at the contemporary songs that have real meaning to people, I think you'll find them as valid today as ever. They are:

Jack's songs and his rules might seem a bit archaic when you apply them to the latest Billboard chart topper, but when you look deeper at the contemporary songs that have real meaning to people, I think you'll find them as valid today as ever. They are:

1. There's a simple and universal story (or concept) that states a desire, and through the singing of song, the narrator is transformed in their desire.

2. All the rhymes are true - but not always easily predicted. No words are rhymed with themselves!

3. There is a perfect balance between repetition of words, novelty, and familiarity in the words and phrases, that is, as soon as the listener thinks they know the pattern, it changes ever so slightly to keep the interest.

4. The melody and the tension and release of the harmony match the meaning of the lyric in position and intensity.With these four rules in mind, I invite you to explore the four perfect songs below.

Today is just another day, tomorrow is a guess

But yesterday, oh, what I'd give for yesterday

To relive one yesterday and its happiness

But yesterday, oh, what I'd give for yesterday

To relive one yesterday and its happiness

When Joanna loved me

Every town was Paris

Every day was Sunday

Every month was May

Every town was Paris

Every day was Sunday

Every month was May

When Joanna loved me

Every sound was music

Music made of laughter

Laughter that was bright and gay

Every sound was music

Music made of laughter

Laughter that was bright and gay

But when Joanna left me

May became December

But, even in December, I remember

Her touch, her smile, and for a little while

May became December

But, even in December, I remember

Her touch, her smile, and for a little while

She loves me

And once again it's Paris

Paris on a Sunday

And the month is May

When Sunny gets blue

Her eyes get gray and cloudy

Then the rain begins to fall

Pitter patter, pitter patter

Love has gone so what can matter

No sweet lover man comes to call

When Sunny gets blue

She breathes a sigh of sadness

Like the wind that stirs the trees

Wind that sets the leaves to swayin'

Like some violins are playin'

Weird and haunting melodies

People used to love to

Hear her laugh, see her smile

That's how Sunny got her name

Since that sad affair

She's lost her smile

Changed her style

Somehow she's not the same

But mem'ries will fade

And pretty dreams will rise up

Where her other dreams fell through

Hurry, new love, hurry here

To kiss away each lonely tear

And hold her near when Sunny gets blue

Hold her near, when Sunny gets blue

And once again it's Paris

Paris on a Sunday

And the month is May

When Sunny gets blue

Her eyes get gray and cloudy

Then the rain begins to fall

Pitter patter, pitter patter

Love has gone so what can matter

No sweet lover man comes to call

When Sunny gets blue

She breathes a sigh of sadness

Like the wind that stirs the trees

Wind that sets the leaves to swayin'

Like some violins are playin'

Weird and haunting melodies

People used to love to

Hear her laugh, see her smile

That's how Sunny got her name

Since that sad affair

She's lost her smile

Changed her style

Somehow she's not the same

But mem'ries will fade

And pretty dreams will rise up

Where her other dreams fell through

Hurry, new love, hurry here

To kiss away each lonely tear

And hold her near when Sunny gets blue

Hold her near, when Sunny gets blue

I peeked in to say goodnight

Then I heard my child in prayer

And for me some scarlet ribbons

Scarlet ribbons for my hair

Then I heard my child in prayer

And for me some scarlet ribbons

Scarlet ribbons for my hair

All the stores were closed and shuttered

All the streets were dark and bare

In our town, no scarlet ribbons

Not one ribbon for her hair

All the streets were dark and bare

In our town, no scarlet ribbons

Not one ribbon for her hair

Through the night my heart was aching

And just before the dawn was breaking

I peeked in and on her bed

In gay profusion lying there

Lovely ribbons, scarlet ribbons

Scarlet ribbons for her hair

And just before the dawn was breaking

I peeked in and on her bed

In gay profusion lying there

Lovely ribbons, scarlet ribbons

Scarlet ribbons for her hair

If I live to be a hundred

I will never know from where

Came those lovely scarlet ribbons

Scarlet ribbons for her hair

I will never know from where

Came those lovely scarlet ribbons

Scarlet ribbons for her hair

I should have listened more and listened well

I should have been your shelter in the rain

I should have touched you more and held you closer

Til I felt it melt your quiet pain

Should I have had more time to spare for you

Should have been there for you, to care for you

With more love, more love

I could have given you the gifts I threw to total strangers

Passing through my nights

I could have cuddled near your gentle flame

Been warmer there than in these glaring lights

Should have had more time to spare for you

Should have been there for you, to care for you

With more love, more love, more love

What would it have taken if only could have taken

My eyes off me for a while

I’d have seen the hurtin hidin,

Just behind the curtain of your smile

Oh, I swear I didn't know, which goes to show

How long it takes a man to be a man

But if I say enough

And try enough

And pray enough

And cry enough

I can still can

Have more time to spare for you

Always be there for you, to care for you

With more love, more love, more love

I should have been your shelter in the rain

I should have touched you more and held you closer

Til I felt it melt your quiet pain

Should I have had more time to spare for you

Should have been there for you, to care for you

With more love, more love

I could have given you the gifts I threw to total strangers

Passing through my nights

I could have cuddled near your gentle flame

Been warmer there than in these glaring lights

Should have had more time to spare for you

Should have been there for you, to care for you

With more love, more love, more love

What would it have taken if only could have taken

My eyes off me for a while

I’d have seen the hurtin hidin,

Just behind the curtain of your smile

Oh, I swear I didn't know, which goes to show

How long it takes a man to be a man

But if I say enough

And try enough

And pray enough

And cry enough

I can still can

Have more time to spare for you

Always be there for you, to care for you

With more love, more love, more love

Epilogue, Craig Tries to Write a Lyric: A Nuclear Disaster

A number of years ago I was hired to write a "classic song" for the video game, "Fallout, A Brotherhood of Steel." In the game, the song plays through a post apocalyptic, 40's era burned out radio.

At this point in my career, even though I had written countless songs (Hasbro, The Little Mermaid Series, et all), I had never attempted to write the lyrics. I always partnered with a dedicated lyricist.

But times and budgets were tight, and in speaking with the audio director from the company, the concept for the lyric was clear and came to me quickly. I decided to go for it. Channelling my best Jack Segal, I painstakingly applied all I had soaked up at his feet.

Perhaps it's foolhardy to put my lyric on the same page with Jack's, but in reading mine below, I trust you can see how all I am doing is paying tribute to the master. Not bad for a first attempt.

A lonely Electron, with nothing to do,

Pairs up with a Neutron for a cocktail or two

Atomic kisses, survived by a few, they had a...

Nuclear Blast!

Said the Electron to the Neutron, you sure can be dense

With this much attraction there's no Civil Defense

Let go of that energy, no need to be tense

Give me that...

Nuclear blast!

Einstein said that space is elastic

Twist his theory, it comes out bombastic

A mushroom cloud, a sight fantastic

Stick your head between your legs, kiss your ass goodbye

A happy Electron, a Neutron its mate

Don't give a damn about apocalyptic fate

They'll party 'til midnight, then boom it's too late, it's a...

Nuclear blast!